‘Wolfpack WORKS Has Helped Me Grow as an Educator:’ Teachers Reflect on Impact of Literacy Initiative as it Comes to an End

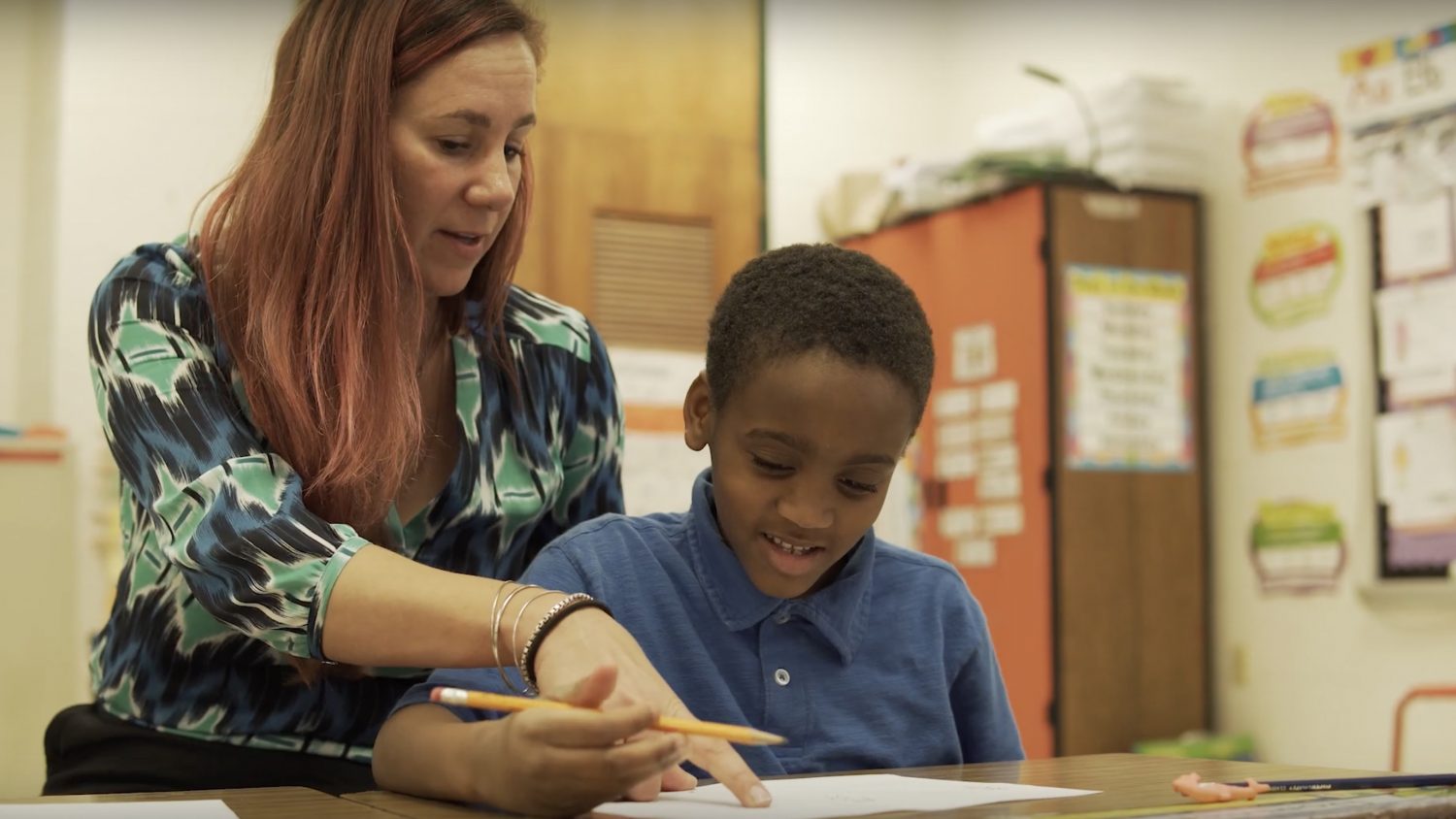

As a first-year teacher, Kelly Mathewson, a first grade teacher at Fred L. Wilson Elementary School in Kannapolis, was always in search of ways to continue to develop her instructional technique to improve her students’ reading proficiency.

She was able to get help in this area by working with a coach from the NC State College of Education’s Wolfpack WORKS literacy initiative, who understood Mathewson’s reflective nature and used that knowledge to help her set goals throughout the school year.

After watching her coach model lessons and co-teaching together, Mathewson would record the lessons she taught on her own, share them with her coach and meet to discuss things that went well and things that could be improved upon going forward.

“Wolfpack WORKS has helped me grow as an educator because it has provided me with the necessary tools, support and confidence to succeed as a first-year teacher. I learned so many different strategies, techniques and lessons from my coach that will help me teach literacy for years to come,” Mathewson said.

Wolfpack WORKS (Ways to Optimize Reading/Writing for Kids Statewide) provided intensive, literacy-specific instruction support to first- and second-year, K-2 classroom teachers in 15 high-need school districts in North Carolina. The initiative, which concluded this summer after three years, has supported about 460 beginning K-2 teachers and about 11,000 K-2 students since it began in 2018 with funding from the North Carolina Department of Public Instruction.

Over the past three years, coaches have helped teachers learn valuable skills such as how to assess students, how to use effective tools, how to use guided reading and decodable texts in lessons, how to use morning meetings to build literacy skills and how to handle difficult conversations with parents.

“Participation in Wolfpack WORKS has helped me a great deal,” said Beverly Rooks Hockaday, a residency-licensed, second grade teacher at Gaston STEM Leadership Academy in Northampton County. “My coach was awesome. She modeled lessons for me, watched me teach lessons and co-taught with me. After each season, we would debrief and come up with a plan that would help both the students and myself be successful.”

Designed around 10 evidence-based literacy practices, Wolfpack WORKS incorporated blended professional development, literacy coaching and resources that beginning K-2 teachers need to implement effective literacy instruction. The goals of this multi-faceted approach were not only to increase teacher knowledge of the science of reading instruction, but to give the teachers the support and tools to put what they learned into practice in the classroom. With intensive, individualized professional learning opportunities, teachers gained the confidence and skills to solve problems in literacy instruction and balance the diverse needs of their students, while meeting other demands on primary grade teachers, such as managing instructional time, working with families and using locally-available technology and curricula.

Based on an independent study conducted by Duke University’s Social Science Research Institute, the majority of Wolfpack WORKS teachers saw gains in their literacy instruction self-efficacy. Growth in this area continued for teachers who participated in multiple years of the initiative.

In addition, 94-97% of Wolfpack WORKS teachers reported a desire to remain in the classroom each year they were surveyed. Helping teachers remain in the classroom is important because Wolfpack WORKS districts had an 18% teacher turnover rate versus an 8% state average when the program started.

Additionally, when Wolfpack WORKS began, nearly half of Wolfpack WORKS teachers were lateral-entry, residency-licensed teachers who had bachelor’s degrees but had not completed a traditional teacher preparation program.

“Whether coming from a teacher preparation program or via an alternative pathway, managing a primary grade classroom and providing research-based, high-quality early literacy instruction is a challenging task,” said Assistant Professor of Literacy Education and Wolfpack WORKS’ Principal Investigator Jill Grifenhagen, Ph.D. “All teachers face a learning curve in their first few years and we sought to help teachers improve the quality of their literacy teaching from day one, problem solve the challenges of meeting diverse student needs and provide support to help the teachers experience success.”

44% average increase in reading proficiency

among 1st grade Wolfpack WORKS students

Duke’s Social Science Research Institute also examined student data on early literacy during the program’s first year (2018-19), which is the most recently-available data on students’ early literacy from the N.C. Education Research Data Center that was used for the independent study. The results suggested that Wolfpack WORKS improved reading proficiency. This improvement was most clearly seen among first grade students based on their performance on Dynamic Indicators of Basic Early Literacy Skills (DIBELS), which measures phonics, phonemic awareness and fluency to provide an overall estimate of a student’s reading proficiency.

Wolfpack WORKS first graders who had lower composite scores on DIBELS-assessed reading proficiency at the beginning of the year, for example, saw greater growth in their reading proficiency throughout the year. Specifically, Wolfpack WORKS first grade students who started the year with a greater literacy need saw a 44% average increase in reading proficiency compared to a 36% change in similar comparison students. In addition, first graders with lateral-entry teachers who were part of Wolfpack WORKS saw a 21% average change in reading proficiency compared to a 9% change among students of lateral-entry teachers in comparison districts.

“Wolfpack WORKS has helped me grow as an educator because it has provided me with the necessary tools, support and confidence to succeed as a first-year teacher.”

Hockaday said that she saw significant growth in reading among the students in her own classroom over the past year, thanks to guidance provided by her Wolfpack WORKS coach.

“As an educator, being in this program has helped me learn how to implement activities to help students grow and learn skills with literacy,” Hockaday said. “I plan to continue to use what I have learned from Wolfpack WORKS and my coach during whole group and small group instruction because I know it works and it provides students with the adequate skills they need to be successful with reading.”

Twenty Wolfpack WORKS coaches worked weekly with and supported beginning teachers like Mathewson and Hockaday, both in person and via web-based tools to assist them in implementing a variety of literacy programs, skills and strategies. The integration of digital tools from the beginning of the project allowed for coaches and teachers to quickly pivot and continue to provide support when schools transitioned to fully remote learning in March 2020 to mitigate the spread of COVID-19.

“I have never been more proud of the work we have done than I was over the past year, as we provided our support and resources to teachers and children in a pandemic,” said Associate Teaching Professor and Wolfpack WORKS Co-principal Investigator Ann Harrington, Ph.D. “Our teachers, coaches, district leaders, interventionists and leadership team members faced so many personal and professional challenges. Nonetheless, we persevered to ensure that the students in our districts received the high-quality literacy instruction they deserved and that our teachers received the support and appreciation that they needed.”

Whether in-person, remotely or a mix of both, Wolfpack WORKS coaches were able to give beginning teachers the necessary tools to impact students in a meaningful way.

Mathewson said one of the most useful lessons she learned from her Wolfpack WORKS coach was how to use a word work-based tool to differentiate readers and how to pair that tool with decodable texts, which reinforce and help students practice certain sound-letter patterns learned through phonics, and guided texts to help students to read at grade level.

“I watched my students improve week to week using this tool and, in turn, it led to better reading levels in guided reading for my students,” she said. “This tool sparked so much growth in my classroom and I will continue to use it for many years of teaching.”

As the Wolfpack WORKS initiative comes to a close, Grifenhagen said she is proud that the project created a shared vision for excellent, evidence-based literacy instruction and enabled beginning teachers to innovate instruction through the incorporation of research and technology, reflect on culturally-sustaining practices and work with families to ensure student success.

Teachers who participated in Wolfpack WORKS, she said, have already received recognition from their districts and schools, taken on leadership roles or chosen to pursue advanced degrees. As these teachers remain in their high-need districts, educating more children and sharing what they have learned with colleagues, Grifenhagen believes that the impact of Wolfpack WORKS will continue to persist.

“The investment in these early-career teachers as professionals will return many-fold as they impact their schools and communities,” she said. “With the excellent early-career teachers we had the honor to work with over the past three years continuing to teach K-2 students to read and write each year, the impacts on student literacy will be exponential.”

- Categories: