Ofelia García Shares Importance of Translanguaging Pedagogies During Linguistic Diversity Speaker Series Organized by Goodnight Distinguished Professor Maria Coady

While the terms bilingualism and multilingualism have existed in education for quite a while, shifting focus to engage in translanguaging pedagogies can be of greater benefit for students who speak more than one language, according to Ofelia García, Professor Emerita in Urban Education and Latin American, Iberian, and Latino Cultures at the City University of New York (CUNY)

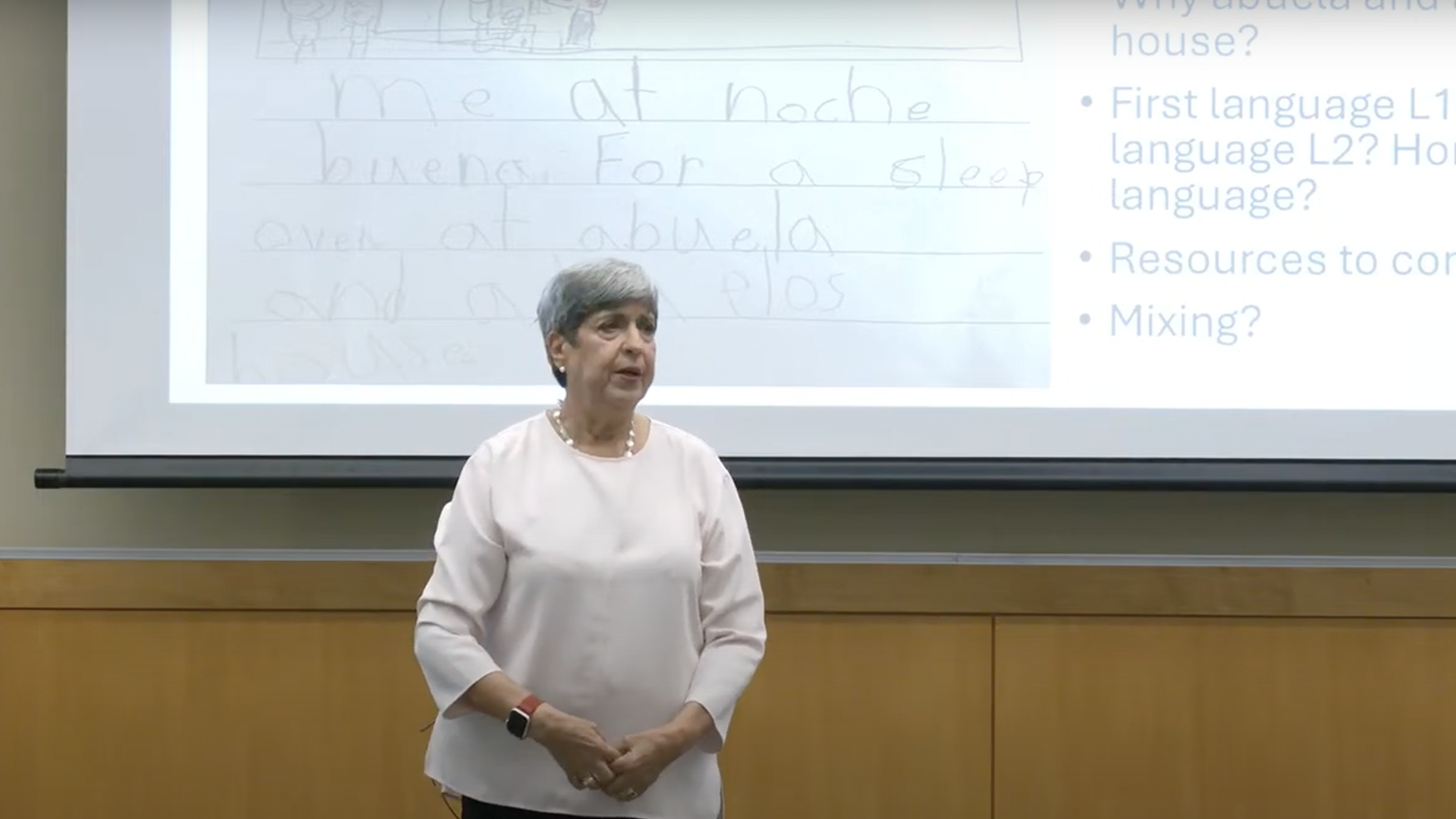

García shared the benefits of translanguaging pedagogies as the keynote speaker at the latest event in the Linguistic Diversity Speaker Series, developed by NC State College of Education Goodnight Distinguished Professor in Educational Equity Maria Coady.

During her speech, entitled “Translanguaging as Practice and Pedagogy,” García shared the importance of using translanguaging pedagogies to provide educational spaces that allow students to represent their full selves and use their entire language repertoire.

“It’s the idea that we no longer focus on one language or the other but we focus on language [as a whole] and our abilities to make sense of the world in the ways we express ourselves,” she said.

Although García noted that translanguaging is not a series of strategies but instead a full pedagogical approach, she shared the following lessons for educators through a series of case studies of multilingual students she has worked with in recent years:

Using Words from Multiple Languages in Writing or Speaking is Not “Mixing”

García shared the story of Paco, a six-year-old boy who, in a journal assignment, wrote primarily in English, but used the Spanish terms Noche Buena, abuelo and abuela when describing how he spent his Christmas break.

Although Paco’s writing followed correct structure, including using capital letters to start a sentence and punctuation to end it, Paco’s teacher recommended he needed remediation for his “mixing,” or use of Spanish words in English writing.

García, however, noted that Paco was not mixing or code-switching between languages, but was drawing on his full linguistic repertoire to refer to specific people or cultural events in his life. For example, the celebration of Noche Buena is culturally different from Christmas Eve and abuelo and abuela are the names he calls his grandparents on that side of his family.

“What this child is doing is using all his resources. He wants to express his whole self, which he could not do if he was using English only,” she said. “In English, he would be leaving parts of himself behind; he would be leaving behind what he does in Noche Buena, he would be leaving behind abuelo and abuela. So, he’s using all of his resources to communicate.”

Build Relationships to Understand Context and Prior Knowledge

García shared the story of Julia, a 10-year-old girl who was born in Honduras to parents who speak Garifuna and Spanish, and was placed in an English language learner class upon coming to New York in 2020.

In her home country and languages, she was interested in and won awards for poetry. One day in class, her teacher was teaching comparisons using the example of “as pretty as.” This made Julia cry, as she remembered a line of poetry her grandmother would recite to her that used that phrase in Spanish.

The teacher could not figure out why the phrase had upset Julia, nor could the other Spanish-speaking students, because they did not have the contextual knowledge to understand her experience with poetry or the connections she was making between the phrases in English and Spanish.

“You can speak the same language and not have the same cultural baggage,” García reminded educators. “You have to be sure that when you walk into your classroom, you’re excited to learn about who your students are. Your students are going to be different. You’re going to want to know what their practices are, and you’re going to have to be a co-learner, not just their teacher.”

All Language Can Be Academic Language

In her final example, García shared the case study of Altagracia, a 17-year-old community college student from the Dominican Republic who was given an assignment in which she and her classmates were encouraged to use all of their resources, including a textbook that was written in academic English, as well as their families, home languages and online research in all languages.

The result was that students were able to bring a variety of cultural contexts and different perspectives into the assignment discussion in class, and were able to communicate their thoughts using terms that spanned languages.

This, García said, while counter to practices used in many educational settings, is an ideal way to acknowledge all that multilingual learners bring to the classroom.

“What we do with our language, if we use it right, is always academic,” García said. “The teacher made sure that the students also consulted their familia and that was important. She also facilitated groupings so students could really talk to each other and think out of the box and encouraged them to use bilingual practices at home.”

- Categories: