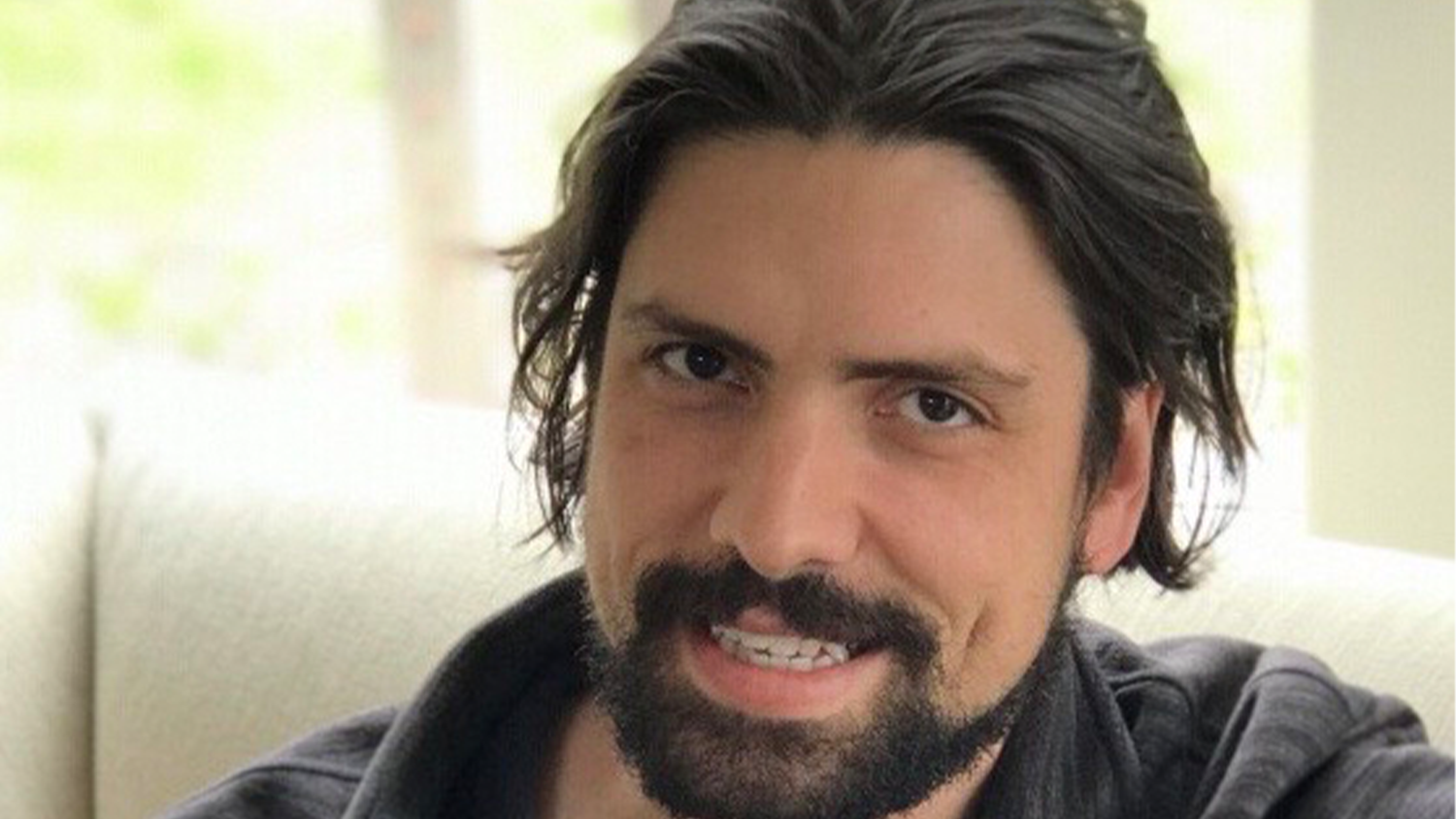

Meet Amato Nocera: ‘I Believe That Learning Happens in Community’

Why did you choose the NC State College of Education?

I really believe in the mission of NC State as a land-grant university. I have already taught a few courses here, and it is clear to me that everyone involved in the College of Education — students, faculty and staff — really care about education in North Carolina. I’m excited to be a part of this environment.

Why did you choose a career in education?

I love teaching and learning. I had my own powerful experiences as a student, particularly in college, where i realized that education was not just about the accumulation of knowledge, but also about the way we see the world. I have long been fascinated by the idea of “ideology” as it relates to schools. One thing that has become clear to me from my experience and study of education is that it is political. Education has the potential to be both a source of liberation — helping students see the world in its full complexity — or, as the famous African American historian Carter G. Woodson put it — a source of miseducation. As educators, we need to interrogate the kind of political ideologies our curriculum represents.

What drew you to your specific field?

I am a historian of American education. One major factor that drew me to this field is that history provides opportunities for examining people in their time and context. Understanding the history of schooling as an institution gives us a window into what our society values now and in the past.

Why did you decide to pursue a Ph.D.?

I went to the University of Wisconsin-Madison for graduate school. The decision to pursue a Ph.D. was a natural one. After college, I worked for several years at the Spencer Foundation, a philanthropic organization that supports research in education. My time at Spencer led me to ask big questions about schooling in America. It also led me to think more about my own experience as a student. My Ph.D. in educational policy studies (history of education was my concentration) was an opportunity for me to continue work I had already begun doing.

What are your research interests and what sparked your interest in that topic(s)?

I study the historical relationships between race and curriculum, white philanthropy and African American education, and social movements and education. I landed on these topics in different ways, often building off previous research I had done on a subject. However, these interests can be traced to my own education. In college, I was an African American studies major. What stood out to me was how different the history I was learning in college was from what I had learned in high school. Not only was it a different perspective on history, but it made me think about the world in a fundamentally different way. I began to question race and power in the world we live in. In graduate school, I started my investigations into race and schooling with these experiences.

What is one research project or moment in your academic career that you are particularly proud of?

I am very proud of a recent article I published in Teachers College Record: “‘More than Equivalent to a Year of College’: Hubert Harrison and Informal Education in Harlem’s New Negro Movement.” It is about Hubert Harrison, an Afro-Caribbean intellectual, activist and educator in New York City during the 1920s. Personally, I find him a fascinating and inspiring figure. But more than that, I argue in the article that he was a central figure operating within a vibrant network of informal education that existed in Harlem — on street corners, in churches, through libraries, and the like — in the first part of the 20th century. This points to the fact that the most powerful forms of education don’t always happen in schools.

What is your teaching philosophy?

I believe that learning happens in community. A lot of my teaching has students engaged in discussion. I also introduce students to non-dominant narratives — the ones that didn’t get in their high school history textbook. I often do this by bringing discussions of race and racism into the classroom, subjects that are difficult for students to talk about, but if properly facilitated, are extremely worthwhile.

What do you hope your students learn from you?

I hope that students come to see schooling in a new way. As many of them are going to be teachers, it is important that they learn to critically examine the institution of schooling and the curriculum. It is also important for students to realize that schools are not separate from the rest of society; they are society. The author Kurt Vonnegut said, “High school is closer to the core of the American experience than anything else I can think of.” This is actually true of the K-12 system as a whole. Both its good and bad qualities are reflections of American society. When students begin to see this, they begin to see their work as teachers in context.

What do you think makes someone an “extraordinary educator?”

There is a lot that goes into being an extraordinary educator. Teaching is a craft that takes years to master. I know from my own experience teaching that I am always learning and improving. But I think at the core of being a great teacher are the qualities of love and empathy. These are vastly underrated aspects of the teaching profession. When I have seen exemplar teachers at work—or read about historical examples of great teaching—it is their care, vulnerability, and empathy with students that has stood out. For me, this is the starting place for transformative education.

- Categories: